By Dr Michael Wynn-Williams – Endometriosis Australia‘s Clinical Advisory Committee

Warning: Contains surgical imagery

Endometriosis is the presence of tissue similar to that of the endometrial lining that grows outside the uterus. It is a chronic inflammatory condition affecting up to one in seven girls, women, transgender individuals, and non-binary people who may not identify as women. Endometriosis of the urinary tract happens when endometrial-like glands and tissue are found in or around the bladder, ureters, or kidneys. In fact, between 20% and 50% of people with pelvic endometriosis have it near the bladder and ureters. It’s less common for endometriosis to directly invade the bladder muscle or ureter, occurring in only about 1% to 6% of cases. The symptoms of urinary tract endometriosis can sometimes be quite general, which can make it tricky to diagnose.

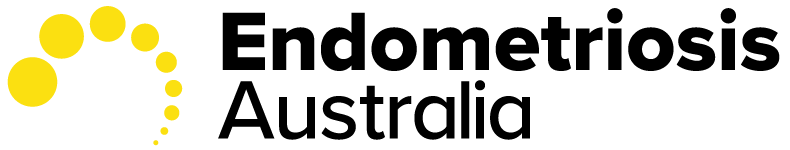

The urinary tract is composed of the left and right kidneys, which gently connect to the bladder in the pelvis via a long tube called the ureter (image 1). Each kidney is about the size of your clenched fist, working as our body’s natural blood filtration system to remove harmful substances and waste, turning them into liquid urine. This urine smoothly travels from the kidneys down through the tubular ureters, where it is stored in the bladder until you’re ready to expel it through the urethra. Endometriosis can impact all the structures within the pelvis, sometimes directly and other times indirectly, leading to a variety of symptoms.

Image 1: The urinary tract, Kidneys, Ureters and Bladder

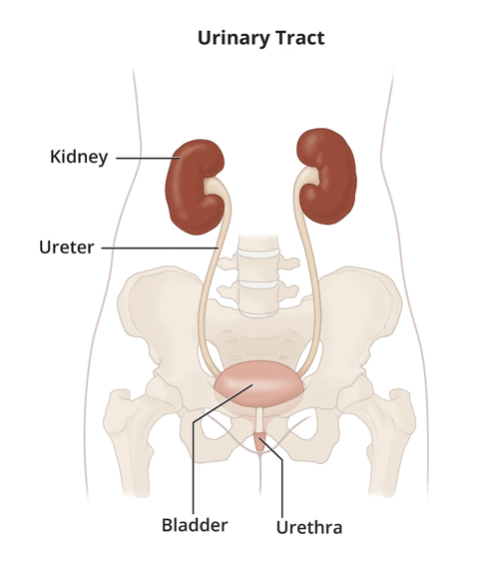

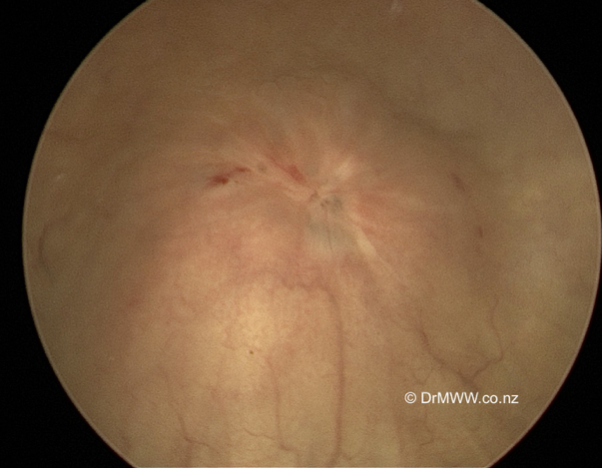

It’s widely recognised that pelvic pain is a common symptom of endometriosis, often occurring before and/or during menstruation or at other times in the menstrual cycle. Many people experience a variety of symptoms related to endometriosis, which can depend on where the endometrial tissue is growing inside or outside the pelvis. The most common way for endometriosis to affect the urinary tract is through superficial lesions on the peritoneum- a thin layer covering all the structures in the abdomen and pelvis, including around the bladder. This type of endometriosis doesn’t invade the bladder muscle itself but instead sits on the surface of the bladder (see Image 2). Sometimes, it can be tricky to tell these symptoms apart from those caused by other conditions. People might feel pain when their bladder is full or while passing urine, or they might experience urinary frequency. These are quite common symptoms of pelvic endometriosis.

Image 2: Extensive superficial endometriosis over the bladder peritoneum

The next most common site of urinary tract endometriosis is superficial lesions that develop around where the ureters travel on both sides of the pelvic walls before they reach the bladder muscle. Just like with other locations, it can sometimes be tricky to distinguish the pain symptoms. The ureters run close to the nerves that control the bladder, vagina, and bowel, so endometriosis there might impact how these organs function in different ways.

Deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) is a less common (20% of endometriosis cases) but very important type of disease we often encounter. It can affect both the bladder and ureter in different ways, each with its own set of symptoms. When deep endometriosis involves the bladder muscle wall, it can lead to pelvic pain that worsens as the bladder fills or empties. Sometimes, you might see blood in the urine during your period or notice it on a urine dipstick when visiting your General Practitioner. Pain can also arise when the endometriosis grows around or into the wall of the ureters in the pelvis, potentially squeezing or narrowing the ureters and disrupting urine flow from the kidneys. This can cause urine to back up into the ureter, stretching it out – called hydroureter. If the endometriosis affects enlarged ovaries pressing on the ureters, it can lead to backup of urine in the kidneys, a condition known as hydronephrosis, which may cause lower back pain and, if untreated, could harm the kidneys permanently. Since we have only two kidneys, prompt treatment is essential to prevent serious long-term health issues like high blood pressure or loss of kidney function. Although it’s very rare for endometriosis to directly grow within the kidney, it can sometimes be found around the kidneys or extending from the liver into the kidney.

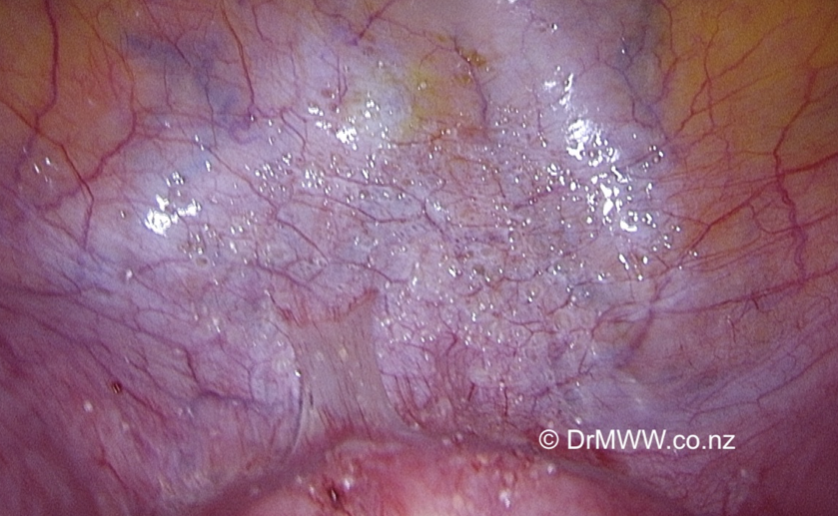

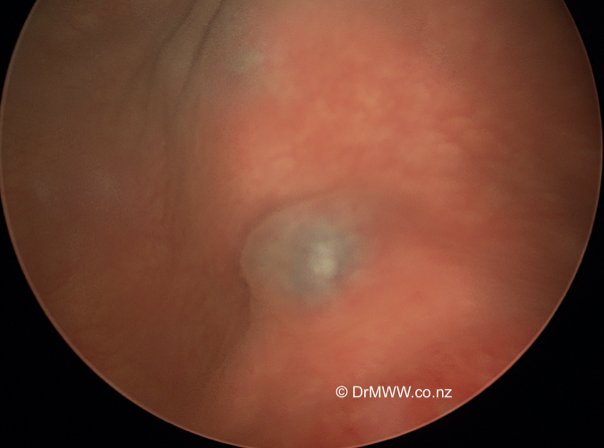

Detecting urinary tract endometriosis can sometimes be tricky. Most cases involve superficial peritoneal disease on the bladder or over the ureter, which often isn’t visible on diagnostic transvaginal ultrasound or other tests. However, with skilled hands—such as experienced Sonographers, Radiologists, or specially trained Gynaecologists and Endometriosis Surgeons—deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) can be seen using transvaginal ultrasound. This includes growths in the bladder wall and around the ureters, which can be identified quite accurately (see Image 3). MRI can also serve as a helpful tool in detecting urinary tract involvement. Remember, though, that a negative ultrasound doesn’t necessarily mean endometriosis isn’t present.

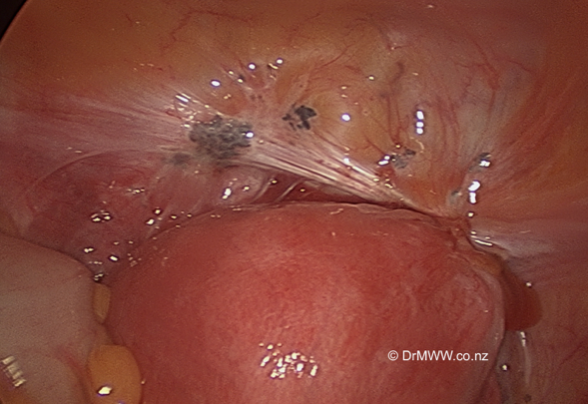

Endometriosis in the bladder is often detected by urologists during a cystoscopy (a camera examination of the bladder) in patients presenting with blood in their urine. (Image 4 & 5)

Image 3: 3cm Bladder deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) nodule seen on transvaginal ultrasound

Image 4: Bladder DIE muscle lesion seen at cystoscopy

Image 5: Bladder muscle DIE lesion seen at cystoscopy, the blue areas represent endometriosis growing through the surface, causing haematuria (blood in the urine)

The doctor who manages urinary tract endometriosis will depend on your specific symptoms. Some people might experience only mild issues or none at all, and their general practitioner can often handle treatment with simple hormonal therapies or anti-inflammatory medicines. Unfortunately, many individuals face a wide range of symptoms that can impact various parts of their lives, including education, work, relationships, sexual health, and fertility. It’s also common for people to find it challenging to get diagnosed, with delays often lasting between 6 to 12 years from when symptoms first appear. However, please know you’re not alone, and support is available.

People seeking care from a Gynaecologist who specialises in endometriosis can find experts trained specifically in diagnosing and managing urinary tract endometriosis. In Australia and New Zealand, these specialists often complete the advanced laparoscopic fellowship offered by the Australasian Gynaecological Endoscopy and Surgery Society (AGES). This additional two-year program is usually done after the RANZCOG six-year training, helping create knowledgeable and skilled doctors ready to handle all stages of endometriosis. Many Gynaecologists also gain substantial experience managing endometriosis without an AGES qualification, showcasing their dedication. Endometriosis specialists typically work within a friendly, multidisciplinary team alongside Urologists and Colorectal Surgeons. For example, urologists may be needed if a ureter becomes compressed or blocked, requiring a stent to help urine flow smoothly, or to check how well the ureter and kidney are functioning. Sometimes, urinary tract endometriosis can occur together with endometriosis in other areas like the bowel, which might mean involving a Colorectal surgeon. All these collaborative efforts aim to offer the best care possible for individuals dealing with this condition.

Management options for endometriosis in the urinary tract are tailored to each person’s symptoms and investigation results. It’s important that the individual remains at the heart of all decision-making regarding their care, with a clear understanding of all available options along with their benefits and potential risks. Additionally, they should have the opportunity to meet and spend time with any other specialists involved in their future surgical care, ensuring they feel supported and well-informed at every step.

Managing endometriosis involves both medical and surgical options. Medical treatments have been discussed in earlier Endometriosis Australia blogs. If these treatments aren’t effective, some people might choose surgical approaches. In cases where the ureter or kidney function is impacted, surgery might be the only practical solution.

Laparoscopic (keyhole) and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopic surgery under general anaesthetic have become standard and effective methods to treat all kinds of pelvic and extra-pelvic endometriosis. Usually, an experienced endometriosis specialist will carefully remove superficial endometriosis from the bladder and around the ureter. For more deeply embedded disease near the ureter, gentle and precise dissection is needed to remove the endometriosis from surrounding structures, including blood vessels and pelvic nerves. If the endometriosis is pressing on or blocking a ureter, a urology surgeon may step in to help by unblocking the ureter or, in some cases, removing and reimplanting it into the bladder away from diseased tissue. It’s important to remove the root cause of the ureter obstruction to ensure the best outcome.

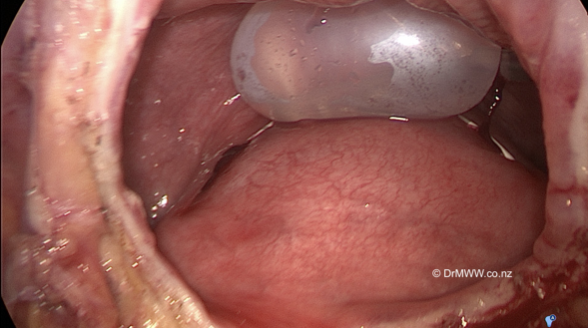

Deep disease that is growing into the bladder muscle wall can be seen by passing a camera into the bladder. The deep disease may then be removed from the bladder wall itself (Image 6). If the inside of the bladder is opened, the hole is repaired with dissolving sutures (Image 7). The patient will require a catheter in the bladder for up to ten days to allow the bladder wall to heal. The patient can often go home after just a few days and will be provided with a leg bag to collect urine. In more severe cases of urinary tract endometriosis, a urologist might place stents that stay in for several weeks to help the ureter heal. In rare instances, a kidney may need to be removed by a urologist if there has been long-term damage from endometriosis.

Image 6: Deep infiltrating bladder endometriosis seen from a laparoscopic view

Image 7: The inside of the bladder (with inflated catheter balloon) after resection of the deep endometriosis. The bladder defect will be repaired with sutures.

People who have had complete removal of deep endometriosis from their bladder and/or around their ureters tend to do very well. Many find their pain and other symptoms improve significantly. It’s important to know that up to 50% of people might experience a return of their pain at some point after surgery. Medical treatments can be helpful afterwards to lower the chance of recurrence and keep pain under control. Your GP and specialist can work together to build a team to support you if you experience any recurrent pain, helping you live a lifestyle that suits your needs and desires. Repeated surgeries should generally be avoided unless absolutely necessary, as their benefits tend to lessen with each additional operation.

People diagnosed with endometriosis are encouraged to learn as much as they can about their condition. This knowledge can help them navigate the sometimes complicated journey of living with endometriosis and pelvic pain more confidently and comfortably.

Written by,

Dr Michael Wynn-Williams

Revised August 2025

Auckland, New Zealand

*this blog has been written in gender-inclusive language